Merchants, Farmers and Others at the St. Lawrence Market

Two Centuries at the St. Lawrence Market

When the Town of York was created, it made space at its heart for local food. The city has moved and its name has changed, but the 210-year-old St. Lawrence Market remains.

To understand the market's place in the early life of the city, it's useful to picture how Toronto's geography has changed. Front Street used to mark the shoreline. Goods like sugar, oysters and oranges, arriving by water, were unloaded on wharves, like Cooper's Wharf at Church Street and Market Wharf at Sherbourne. There was an informal fish market on the beach where Berkeley Street is now.

On Saturday, November 5, 1803, Toronto saw its first official weekly market day in a place established by Lieutenant Governor Peter Hunter "for exposing publicly for sale, cattle, sheep, poultry, and other provisions, goods, and merchandise, brought by merchants, farmers and others, for the necessary supply of the said Town of York."

The first market was simply an open space with a few wooden sheds. Henry Scadding's wonderful 1872 reminiscence, Toronto of Old, tells us that it was 36 by 24 feet "running north and south" between the streets now named Front, Jarvis, King and Church; more or less the location of what we now know as the St. Lawrence North Market.

Besides the imported produce coming in by boat, early Toronto was well supplied with farm produce grown in the surrounding countryside. "Toronto, even a hundred years ago, didn't go past St. Clair," points out Toronto historian Bruce Bell, who runs market tours. The market also sold a lot of wild game, including deer (brought in on winter sleds by First Nations hunters), as well as game birds and even bear.

Produce came into the city along Yonge Street and a few other major roads regulated by toll booths. The website for the preserved Tollkeeper's Cottage at Bathurst and Davenport informs us that by 1851, a penny toll was charged for every twenty head of cattle, sheep or pigs driven into town. (Of course, for many decades, cattle were brought to market "on the hoof"; before refrigerated vehicles, there was no point slaughtering them on the farm and hauling the dead meat over poor roadways.)

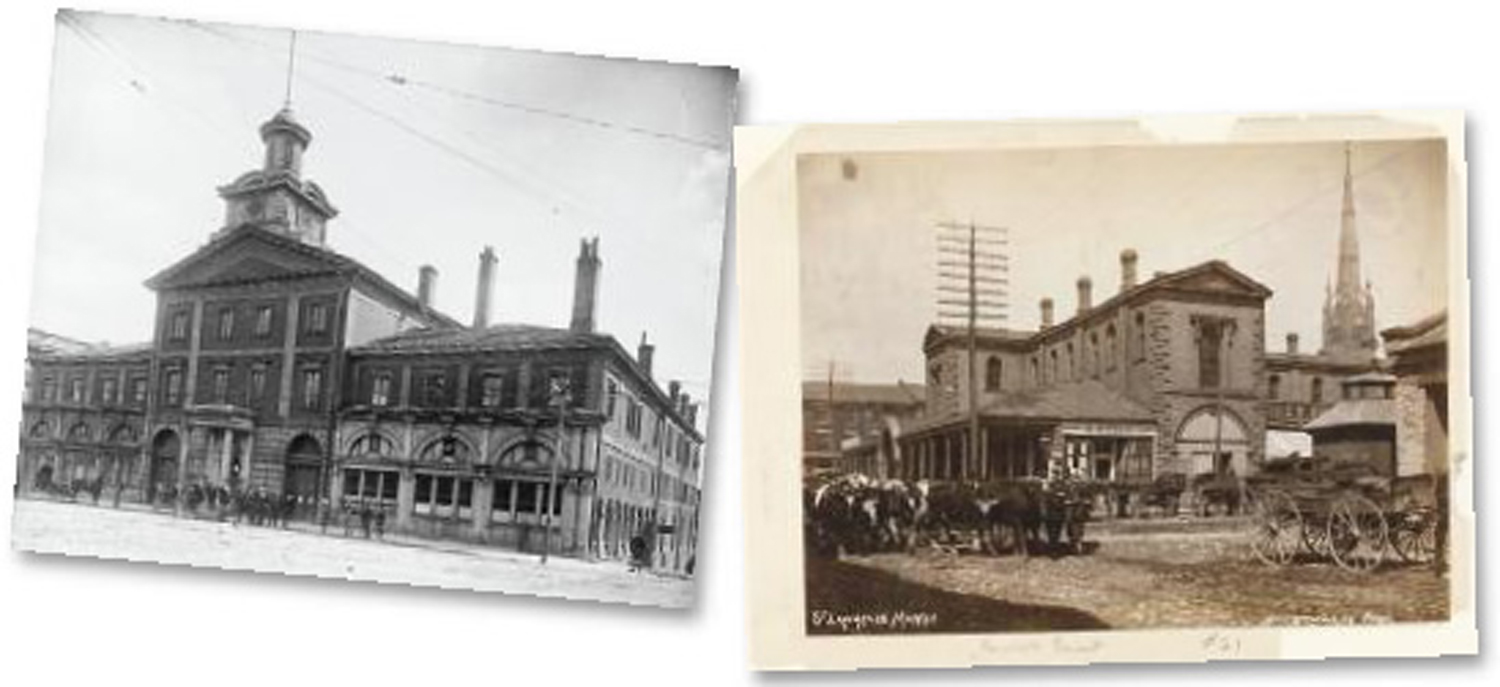

In 1824, the market was enclosed with wooden pickets along its east, west and south sides, so the main entrance faced King Street. In 1831, a red brick market building was built on the site. Its three-story central block faced King Street, topped with a cupola and a clock tower. On each side was a two-story wing with arched entrances for the merchants' stalls; they faced King Street on the north and Front Street at the back. Butchers' stalls topped by a wooden mezzanine ran all the way around the interior, enclosing a large rectangular courtyard that was open to the sky.

In 1845, the city government moved into the second floor of the market, but in 1849 it was severely damaged in a fire, so it was demolished and replaced by the still-existing St. Lawrence Hall to house city business, with a new, covered, version of the market building to the south of it extending to Front Street.

Meanwhile, the city was growing in all directions. "In about 1854, the shoreline was moved down," says Bell. "In the 1850s, they needed room to put the trains, and City Council voted to give them access. That's when The Esplanade really became the harbourfront of the city. The boats would load everything onto the dock and [horses would cart them] right through those old beautiful warehouses and onto Front Street."

Food manufacturers clustered in the market neighbourhood in the Victorian era. William Davies had his main office at 145 Front Street East; his meat company would become Canada Packers, then Maple Leaf. Francis A. Shirriff, who concocted ingredients like vanilla extract and baking powder at 106 Front East, went into business with Thomas G. Bright, who made ginger wines and syrups at 84 Front East. Together, they founded two companies. When they divided up the firms, Shirriff's became famous for its marmalade and instant puddings, pie fillings and potato flakes, while Bright's became the biggest wine company in Canada.

In 1899, when Toronto opened its new city hall (our "old" one) at Bay and Queen, the aging market building north of Front Street was completely demolished and a grand new pair of matching buildings was constructed. The new South Market was the first St. Lawrence Market building south of Front. "It took two years to build it," says Bell.

The North and South Markets made a matching pair connected by a steel and glass canopy that spanned Front Street. It was not removed until 1954, the year the Toronto Food Terminal opened and shifted focus away from the market as the primary food supplier for the city. This was the time when more processed convenience foods were becoming commonplace, and no doubt there was a sense that Toronto should be turning away from a pair of buildings that were built on a slope to accommodate the drainage of blood from slaughtered animals.

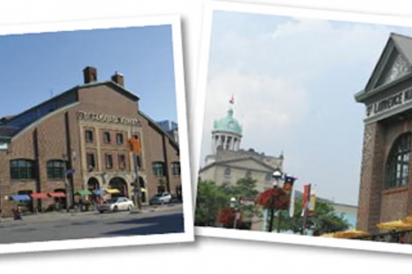

In 1967, there was apparently no public outcry when the North Market was torn down and replaced with the far less evocative structure that now stands. So in 1971, the City was all set to demolish the South Market and redevelop it... except that something odd happened: the public said no. "David Crombie, Jane Jacobs, John Sewell and that crew saved it," says Bell.

"It was a real mess; no one lived downtown, there were all these warehouses," he says. "They were going to tear down the Flatiron Building, too." Instead, the South Market was renovated in the 1970s and the City opened a museum and archive upstairs, echoing the earlier use of the North Market building.

By the early '80s, you could no longer buy a live chicken at the St. Lawrence Market, but it still retained some of its old earthiness. My own partner Jonathan St. Rose, who was cooking for the Montreal Bistro at Adelaide and Sherbourne in those days, made frequent runs to the market to pick up "brown rice, a bunch of tenderloins," he says. He remembers a much darker space with wooden counters and antique balance scales. "Now it's got these nice straight corridors; back then there'd be a stall here and another stall there," he says. "Now you have year-round everything; back then you'd [ask for something] in the winter and they'd say 'Oh no!'"

"You'd watch them make ten sandwiches, and every sandwich would be different," he says. "Often you'd see guys in chef or sous-chef uniforms walking around, picking the food. And it was always a hangout for street people; they'd do little chores for food—sweep the floor, take out the garbage."

For good and ill, increased regulation means that granny at home is no longer cooking up the shops' daily specials. Weekly fish deliveries have changed, too. "You could smell it," says St. Rose. "You always had the cats—they knew it was fish day." They appeared at night to enjoy the fishy "scraps and blood and water," he recalls. "And you could smoke in the market!"

Today, some people on Bell's tours are unnerved to see "a slaughtered lamb with the eyeballs still in coming in on the pushcarts," he says. "That's one of the true links we have to our history: the food is presented the way it was two hundred years ago. Carrots in baskets and, of course, slaughtered animals, which you don't see at Loblaw's. Especially kids who are on their iPads all the time—a lot of them scream, but they do appreciate it, too."

"There's a vibe that comes with the building; there's an ethos," says St. Rose. "There's a stream of continuity that hasn't been disrupted."

Recently, the St. Lawrence Market topped National Geographic's list of world food markets. Meanwhile, the North Market is facing yet another redevelopment, stalled for several years over its projected $91.5 million price tag. It will be up to people who care about their food sources to safeguard the market for future centuries by speaking up for it from time to time... and by exploring what it has to offer today.

St. Lawrence Market

93 Front St E, Toronto, ON M5E 1C3, Canada

+1 416-392-7219