All About Melons

The Montréal melon provides for a great historical look at the progression of food in North America. Origins of this variety of melon can be traced back to 1694 when Jesuits brought melon seeds to Montreal from France. They saved seeds and crossed them with other varieties. (In the Montréal melon I can detect aromas of the famously perfumed French Charentais melon and the nutmeg notes of the then popular New Jersey Hackensack.) By 1870, an exceptionally large, tasty, aromatic, green-fleshed, delicately laced and thin-skinned melon was perfected by the Décarie family. It soon became the most widely planted melon variety in the eastern, short-season regions of North America.

But the Décarie family farm remained the most renowned producer. Their secret was to preheat their beds with fresh horse manure, start the plants under glass cloches, and carefully prune the plants as they grew. Then the delicate melons were harvested only at full maturity and laid into custom-woven baskets for delivery on high-speed trains. They appeared on hotel menus in New York, Boston, Chicago and Montreal for over $1 per slice (more than the price of a steak).

Their demise came about due to the opening of new railway lines to the mining areas of Colorado. A much smaller, grassy tasting, minimally aromatic yet sturdy Rocky Ford variety (still available today) thrived in the arid western climate. It could cheaply be shipped east. Sadly, most consumers remained satisfied with this meagre alternative.

For decades it was thought that the Montréal melon had gone extinct, but Montreal fruit breeder Ken Taylor discovered in 1995 that seeds from this old muskmelon variety had been preserved and stored at a USDA seed bank in Iowa. The variety was subsequently brought back to life. If you desire the heavenly experience of this superior melon, you will have to find a local grower or just grow them yourself.

Historical Record

The sweet berries commonly called melons originated as gourds in Africa. For millennia they have found their way around the world to be nurtured into forms now known as:

- African seedy watermelons (lanatius): hairy stems

- Middle Eastern thirst-quenching cucumbers (sativus): cultivated

- South Asian bitter melons (momordica): biting, seeds

- American squash (cucurbita): gourd

- European aromatic cantaloupes (cantaluperia): originally from Cantalupo, Italy

- North American muskmelons (reticulates): laced/netted skins and a musky aroma

- Asian, Casaba, Galia and Honeydew melons (inodorus): smooth skins and no musky aroma

Since melons so readily crossbreed (both purposely and inadvertently), there are no reliable records of their development. The earliest pictorial record of a melon is an Egyptian image of something that looks very similar to modern-day Armenian cucumbers. Botanically these are melons; but culinarily they are now used as cucumbers. To simplify this article about melons, however, I will only discuss the sweet melons typically enjoyed fresh and raw.

Melons were enjoyed by the Greeks and Romans and during the European Renaissance. But descriptions and images do not sufficiently identify what varieties they had; and to further confuse historians, they were named after the regions in which the melons were grown. Whatever they grew, melons were widely enjoyed.

One of the first named varieties was for Jenny Lind, the famous Swedish opera singer, in honour of her coming to North America in 1850 to sing in almost a hundred concerts for legendary showman P. T. Barnum. This tiny delectable melon, with a distinctive button on its blossom end, is still available today.

Watermelons were originally developed for their nutritious black seeds. But nowadays they are enjoyed around the world for their sweet red (or yellow, orange or white), grainy flesh. You can still chew the seeds. Pollinating a sterile triploid version with a normal diploid version of watermelon is the way seedless versions are created.

Asian melons, such as bitter melon, are typically not sweet enough to be considered fruits. Instead they are used as a base for flavoured pickles and sweetened candies. Sweeter versions such as Casaba, Honeydew, Galia, Canary and others make up for their less intense flavour with a long storage life. They are not normally grown in cooler climates because they require a long (120-day) growing season. Some have been crossed with more flavourful, shorter-season varieties to make them suitable for northern gardeners. Green-fleshed Diplomat is one of the most successful of these.

Cantaloupes were perfected in the 1800s in Cantalupo nel Sannio, Italy, the site of a former papal country villa near Rome. The best known of these are now the French Charentais, or Cavaillon, and the Japanese Yubari (which sell for thousands of dollars). True cantaloupes are not typically marketed in North America.

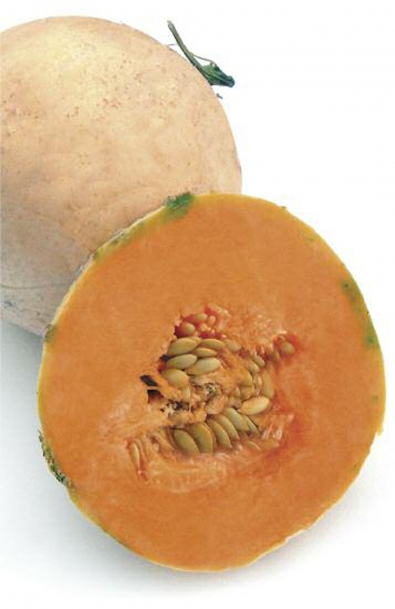

Muskmelons were so well received by Native Americans that they spread west, well ahead of the European settlers. Today they are (incorrectly) identified by the more appealing Cantaloupe moniker. They still grow quickly, store and ship well, and have at least some of their lovely musky aroma. Their netted skin conveniently camouflages cosmetic flaws.

Quality Growing

The secret is to trick your plants into thinking they are growing in the lush tropics. Steady heat, lots of water during growth and little during ripening, balanced fertility, and no weeds, insects or diseases will create an amazing perfume. This is not a project for neophyte gardeners.

Select the varieties you wish to grow. For a first venture, I suggest one of the standard F1 hybrid "cantaloupes" such as Halona for early harvesting and Athena for later harvesting. For watermelons, the small round Sugar Baby and oblong Sweet Favourite are reliable choices.

In the second week of May, mix a ratio of three-quarters potting soil with one-quarter of your own topsoil and pack this into 4-inch peat pots. Plant two seeds per pot, water well, and move them to a sunny window. At the same time, rake compost into a 3-foot-wide growing bed in your garden and water well. Dig a trench around the edges and lay on a sheet of clear lightweight construction plastic. Do not use black plastic, which would cool the soil. Tightly seal the edges in the trench with soil. (Solar heat kills the sprouting weeds.) After the young plants are up and growing, pinch out the smaller plant to leave the larger one in the pot. Move the plants to a sunny, wind-protected outdoor area whenever the days or nights are forecasted to be warm.

After the first June cold spell has passed (around June 7), cut a single row of 4-inch crosses into the plastic sheet, about 30 inches apart. Carefully scoop out enough soil to accommodate the peat pots and then fill each hole with water. After it has drained away, gently slip in a peat pot with its single melon plant and push the soil into full contact with the peat pot. Insert some 6-foot hoops over the plants and plastic. Cover with a breathable row cover and seal in the edges. This not only keeps the plants warm, it also keeps out cucumber beetles that could be a vector for lethal bacterial wilt.

About ten days after the first flowers (the males) appear in early July, remove the cover. I like to cut the plastic sheet down the middle and slip it completely out and then discard it. Shallowly cultivate the soil to remove any weeds and to make sure the roots receive plenty of air. The fruiting flowers (the females) should now be about ready to open. Each one is fertile for only a couple of hours on a single day, so make sure the bees can get to the flowers whenever they are ready for pollination. The more bee visits, the larger the fruit.

When a main lead on any plant gets over 3 feet long, pinch it off. While the plants are growing and setting fruit, water 1½ inches per week (twice the usual amount). After the usual three to four fruits have set, stop watering and pray for dry, sunny days. Put a clump of straw or a piece of wood under each melon to keep worms from burrowing into it. Pinch off any late-setting fruits. Mildew on the leaves simply means that the plants have finished their work.

Now comes the most difficult part: harvesting the fruit just as it fully ripens. (There is no point in picking it a week early like the commercial growers do; the fruit softens after picking, but does not continue to ripen.) The first sign that maturity is near is when the green skin turns tan-coloured. Modern hybrids are ripe when the stem easily slips off. I prefer to select fragrant melons on a calm evening simply by using my nose. Alternatively, observe the last tendril or tiny leaf just before the melon; if it has turned brown it is another good indicator. Thumping on the melon (especially a watermelon) and hearing a dull echo indicates ripeness, while a ringing indicates immaturity. Another good gauge is to look at the underside: yellow indicates ripeness while greenish-white tells you to come back in a few days.

Melon with a little something salty

Chefs become excited when presented with a basket of perfectly ripe Charentais melons. Then they become hesitant when told the price. But they quickly buy them after just a whiff. And then they realize their customers do not understand the difference between a usual melon and a memorable one so they feel they have to present something more exciting on the menu, often melon with prosciutto (or smoked salmon, or an assertive cheese). Secretly, the chef is hoping not to sell too many; tomorrow's lunch could be the perk of half a melon with absolutely nothing on it.

If you only have access to a regular melon, something salty is always a fine addition. If your melon is not good enough even with this, some freshly grated nutmeg, a brush of honey, and a drizzle of lime juice and zest may save the day.