The (Sometimes) Fruitful Work of a Fruit Breeder

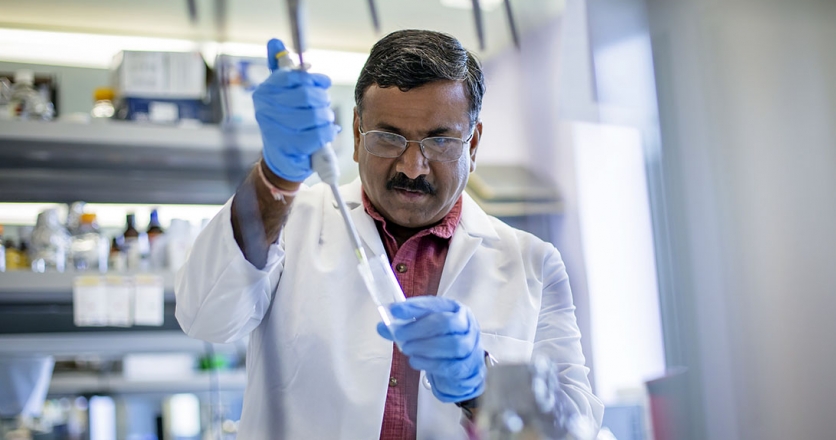

When bees start to work in Niagara's orchards every spring, Jayasankar Subramanian is right there alongside them. Wielding a fine artist’s paintbrush or his fingers, the fruit-breeding scientist plays Mother Nature by delicately touching pollen harvested from one bloom to the sticky stamen of another, with the hope that a fruit — a peach or a plum, specifically — will appear in a few months.

Sometimes it’s cold. Sometimes his fingers go numb. Sometimes it rains the next day, making his painstaking efforts all for naught. Still, for the last 17 years, Subramanian has persevered with the hope his efforts will produce a stone fruit that will be the apple of farmers’ and consumers’ eyes.

Subramanian is a tree fruit breeder with the University of Guelph, based in Vineland in the Niagara region. His life’s work is to play the role of the birds and bees, but with a scientist’s mind, to develop new varieties of tasty and disease-resistant peaches and plums that could become the next Redhaven or Baby Gold.

And by life’s work, it can take an entire career to develop a new fruit variety worthy of space on a supermarket shelf.

“That’s the ultimate feeling for a fruit breeder — when you walk around with your grandkids and see varieties you bred on store shelves,” Subramanian says. “That variety that everyone is growing and eating — that’s the reward you get for the work.”

Back in the orchard every spring, though, Subramanian is just grateful if his bee impersonation is on point. And, of course, if Mother Nature cuts him a bit of slack. Those early days in a growing season are difficult and can be heartbreaking if the stars — or the jet stream — don’t align.

“If we [pollinate], say, 50,000 flowers, if we’re lucky, there will be 600 to 700 fruits, if we’re lucky,” Subramanian explains.

In bad years, he’s wound up with as few as 15 potential candidates for the next great peach or plum. Sometimes, there have been none thanks to bad luck or untimely rains that send another year’s work down the drain.

“Everything gets washed out and there won’t be any set. That’s happened to me two times,” he recalls.

That’s just with peaches. Plums are even more fickle, regardless of the forecast. The pollen of some varieties is incompatible with others; something Subramanian doesn’t always know before heading into an orchard to play matchmaker with his flower dust and paintbrush. It raises the question: why would anyone want to be a tree-fruit breeder when it can be so fruitless a venture? Ask Subramanian and he’ll tell you with pure altruism that he’s trying to get better produce to Canadians.

On a more personal level, though, his reasons for wanting to discover the next great stone fruit trace back to his childhood in Tamil Nadu. The South Indian state is known mostly for growing grains, but within a short drive from sea level to 5,000 feet up the Nilgiri Mountains and the Western Ghats, growing conditions can morph from bone dry desert to temperate and produce everything from pulses to mangoes.

But it was the region’s tea and coffee plantations that piqued his interest, even though he grew up only seeing photos of them. “There was nothing surrounding me, but I used to see pictures in documentaries and they were always very beautiful to look at. They gave me a sense of peace to look at them,” Subramanian remembers.

He enrolled in horticultural science at the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University and spent a month at a coffee plantation, learning how to turn a tangled jungle into one of those picturesque, cultivated estates. He got hooked on horticulture, and fruit in particular, eventually doing his PhD in mango-breeding and a post-doctoral fellowship working with grapes at the University of Florida.

In 2002, he saw a posting for a tree-fruit breeder with the University of Guelph, a job that would split his time between the classroom on campus and a lab and orchards in the Niagara region.

“I had seen peaches and plums in India, but that was a classroom setting,” he says. Nonetheless, he applied and landed an interview.

Well aware of his limited exposure to Niagara’s agricultural flagships going into the meeting, Subramanian was honest about his experience. But he did have that post-doc work with grapes to hold him in good stead and, ultimately, he got the job.

He was tasked to come up with new varieties of peaches and plums, inheriting about 3,000 test seedlings from his predecessor that he would have to cull and sort the plum candidates from the duds. All the while, he continued to breed new fruits to keep the proverbial research pipeline flowing.

At the time Subramanian was hired, he was asked to develop the penultimate processing peach for the CanGro canning factory in nearby St. Davids. The operation wanted large fruit that would provide a certain number of slices to fit into each tin coming off the line. The fruit had to be disease-resistant, too. No one fussed over flavour because sugary syrup would cover any flaws.

Subramanian’s focus changed in 2008 when CanGro permanently closed. With the shut-down of the 100-year-old fruit-canning factory, so did the local commercial peach-processing industry.

“Then we had to make a 180-degree turn. Then we had to look for fresh-market peaches,” he explains. “In fresh-market peaches, the fruit has to look good, taste good and smell good.”

These days, he’s developing white peaches, those paler, floral-scented cousins of the yellow peach favoured by Asian consumers in Canada’s increasingly diverse consumer market. Growers are also clamouring for more nectarine varieties to satisfy those with an aversion to peach fuzz. Millennials, in particular, are hungrier for nectarines than any other generation, Subramanian notes.

When it comes to plums, he’s merely trying to get more of us interested in this less appreciated cousin in the stone fruit family. Among his plum progeny are yellow European plums — YEPs for short — which, thanks to a genetic mutation, boast all the antioxidants of their blue cousins without the bitter skin. Finding new varieties that ripen earlier or later in the growing season means more fruit for us and more profit for the farmers growing them.

“The consumer is key. [If ] they like it, the farmers will grow it, even if the farmer doesn’t like it,” Subramanian says. “But at the same time, it should be farmer-friendly and not have too many operational expenses."

Even if he finds a winner, it will take years to get it to market — a decade at least — considering the time needed to propagate it, test it in orchards and glean consumer feedback, then encourage large-scale planting. That’s followed by another few years’ wait for seedlings to mature enough to produce a crop.

The people who study tree fruit are as rare a breed as the stone fruit darlings they pursue. If you put all the tree-fruit breeders in North America together, Subramanian says you might fill a classroom. Grain breeders, by comparison, could fill an entire college campus.

But they’re in it for the long haul — no matter how cold it gets on those spring days spent in an orchard doing the gentle work of a tiny insect or the rain that might undo those efforts.

“It’s very patient work,” Subramanian says. “The first time you see a new variety, you get really excited.”

University of Guelph Vineland Research and Innovation Centre

4890 Victoria Avenue N., Vineland Station, Ont.

vinelandresearch.com | 905.562.0320