The Moon and the Stars

Across Canada, it’s a rule: Don’t bother planting your garden before the May long weekend or you’ll risk losing it all to frost.

At Earth Haven Farm, just north of Belleville, Aric Aguonie and his mother, Kathryn Aunger, have a different approach. They also pay attention to the moon, the planets and the stars. Depending on where in the sky these bodies land, it could mean it’s time to plant their root crops. On another day, the cosmos might be lined up in favour of leafy vegetables. The same goes for fruit and seed crops. They even schedule the spreading of compost and cattle manure according to the lunar calendar.

Aguonie and Aunger run a biodynamic farm and sell their produce at Evergreen Brickworks and The Village Market in Richmond Hill.

Paying attention to what’s going on in the sky is not the only thing that defines biodynamic agriculture, but it’s an important component of the practice.

A lot of what goes on in the cosmos affects how plants grow or reproduce,” Aunger says. Of course, weather is a factor too, she adds, but a fine-tuned understanding of the sky will go a long way.

Farmers such as this mother-and-son duo are rare. Demeter Canada, the certifying body for biodynamic agriculture, counts Earth Haven’s 200-acre farm as one of only 34 in the country. Though few, the gamut runs from traditional crop farms, to vineyards and livestock operations.

In short, biodynamic farming means embracing holistic and sustainable agriculture. These farms are whole ecosystems and considered as one complex, self-reliant organism. Respect for each of its components — the soil, the waterways, the plants, the animals — is key.

The idea is believed to first have originated with Austrian philosopher and esotericist Rudolf Steiner, early in the 20th century, at a time when industrial agriculture was making large leaps. He encouraged farmers to look for alternatives to the rising tide of monoculture.

But Steiner’s farming philosophy isn’t new. Companion planting, composting, manure fertilization and rotating crops are concepts that date back to the dawn of agriculture. Keeping an eye on the cosmos is also part of ancient traditions.

“I like to tell people that the sun comes up every day. That alone affects us,” Aguonie says. “It’s the first evidence that indicates things out there in the cosmos are affecting us.”

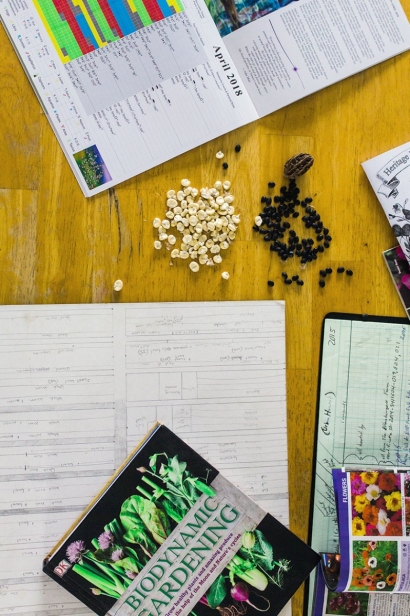

To help farmers understand the complexity of moon and planet phases, Aunger publishes the celestial planting calendar annually with the co-founder of Earth Haven Learning Centre, Rosemary Tayler. She explains that four plant groups — leaf, blossom, fruit and root plants — are in separate categories because the moon affects them in different ways.

“Each month of the calendar gives daily recommendations for planting, harvesting or working in the garden,” Aunger says. “One day might be a leaf day, another a root day, another a flower day and another a seed day. Other days, the garden should just be left alone. Each month is mapped out with complete details to assist everyone from the backyard gardener to large-scale farmer or vintner.”

Planting calendars have been around for a long time. The Farmers’ Almanac has been in print since the early 19th century and, like the celestial planting calendar, it relies on lunar, solar and planetary positions. The Earth Haven Learning Centre, opened in 2016 by Aunger and Tayler, gives curious folks the opportunity to take educational workshops and seminars on biodynamic farming.

“When we teach it, we encourage people to make note of what they’re doing on their own garden plot, and then follow up by asking themselves… ‘Does it work?’” Aunger says.

That very question — does it work? — can be touchy, not just as it relates to celestial planting, but to biodynamic farming as a whole.

It can seem esoteric and has not benefited from the same degree of outside research as organic agriculture. However, much of what comprises organic farming is included in biodynamic farming. Given its strict policy on pesticides, herbicides and fertilizer, it is fair to expect similar conclusions: for instance, that it can help cut greenhouse gas emissions and help avoid nutrient run-off.

In the case of Chris Boettcher, a long-time biodynamic farmer and chair of the Society of Biodynamic Farming and Gardening in Ontario, numbers back up his experience. He has been testing his soil since he began using biodynamic methods.

“When I switched over from a conventional system to a biodynamic system about 20 years ago, my soil was at 4.6 per cent organic matter. Now, it’s at 8.9 per cent, which is pretty well unheard of here in Huron County.”

He adds that in his county, conventional farms are losing organic matter in the soil due to irrigation and erosion, something biodynamic farmers avoid with their practices. A soil rich in organic matter is more fertile. It can also contribute to carbon sequestration — the process where harmful carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere.

Boettcher, who studied agriculture at Guelph University, was a conventional farmer before he turned to biodynamics. He has a deep interest in the science of his profession, but also acknowledges — and embraces — the more spiritual side of biodynamic agriculture.

“Maybe we should treat food like something sacred. The drive-thru at Burger King doesn’t cut it anymore,” he says. To produce food is “a sacred profession. There’s love and emotion here.”

Biodynamic farming is not only a guarantee of quality, but of farming practices, argues Laurie McGregor, the administrator at Demeter Canada.

“Standards fall in line with kosher and halal standards, because of the humane treatment of the animals,” she says.

McGregor admits she and her colleagues have had to fight back against notions that biodynamic farming is a little airy-fairy. But she defends the practice by explaining that many of the Demeter certified farmers, such as Boettcher, are educated in agriculture. Others have gone to Europe, where the practice is strong and well rooted, to learn from farmers there.

Boettcher adds that when he switched to biodynamic agriculture he became a “real farmer.”

“Observational skills are so much more important," he says. "You really have to be on the ball and have that intuition." Observation, intuition and mindfulness are key to the way Aguonie, at Earth Haven Farm, operates.

Originally, he was hoping to raise bison. Careful consideration and taking his time observing his surroundings steered him in a different direction.

“The first year, I just walked around the farm, meditated, tried to learn about the people who were here before me. I looked at the hedgerows, the barn, the various systems that they had used.”

A less careful farmer might have seen those hedgerows and decided to bulldoze them for convenience, Aguonie says. As a biodynamic farmer, he considers them an integral part of the organism. “If you don’t take the time to figure out why the hedgerows were there in the first place — for protection against wind and erosion — you’re destroying a whole ecosystem.

“When I walk on our property, I have a real respect for the people who farmed this land a hundred years ago,” Aunger adds. “When I see these humongous boulders that are 10 feet across, which they moved up against the hedgerows with a team of horses, I think, my goodness, these people… They were dedicated to making this land work.”

Earth Haven now grows garlic, black beans, shitake mushrooms and Tuscarora white corn — also known as Iroquois white corn, an ancient heirloom variety.

Their respect for the earth kept Aguonie and Aunger from making a mistake — raising bison — which would have put too much strain on the land.

Aguonie also learned that there were too many predators for smaller animals such as sheep. All this deliberation led him to Scottish Highland cows, which they butcher once or twice a year. They also sell tallow and soap made from the cow’s tallow at farmers’ markets.

“I’m stuck with them… and I love them,” Aguonie quips about his cows.

Earth Haven Farm

1619 Vanderwater Rd., Thomasburg, Ont.

earthhaven.ca, 613.478.3876