Bean-to-Bar

Eating chocolate can be good for the heart. Toronto bean-to-bar makers want to ensure it’s also good for the soul.

We’re heading into a delicious season of sweet gifts and delectable indulgences. And as consumers increasingly consider origins and ethics around the food they buy, bean-to-bar craft chocolate is gaining popularity as a treat people can feel good about.

Toronto makers and purveyors, including SOMA Chocolatemaker and ChocoSol Traders, can answer customers’ questions about where and how the cacao in the products they’re buying was grown. They know the farmers, have ongoing relationships with them and buy directly from growers for a price well above the $2.50-per-kilogram Fairtrade International-set price for beans.

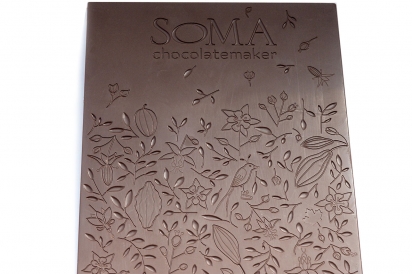

“Labels like ‘fair trade’ and ‘organic’ are substitutes for education and relationships,” says Samantha Luc, who handles tastings, tours and education events at SOMA, the Toronto chocolatemaker started by David Castellan and Cynthia Leung in 2003.

“I think the work falls on us to tell the stories of the people we’re working with, to make them not only seem real, but like they deserve a fair wage,” Luc says. The majority of the world’s cacao beans, which are turned into chocolate bars and confections on store shelves, are grown on small jungle family farms in the crop-ideal climate zones of West Africa, primarily Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana.

Because of the prevalence of child and forced labour in these regions, people are starting to ask questions about the human cost of an inexpensive treat.

And there's good reason to do so. A joint 2015 Tulane University- U.S. government study found that more than two million children were working in “hazardous” cacao production conditions in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana.

ChocoSol founder Michael Sacco says the company’s “horizontal” trade relationship with farmers goes beyond economics. It's personal and it's based on a “social enterprise model” that includes reciprocal ChocoSol staff visits to farms and reforestation projects to help communities, including planting thousands of trees.

Both Sacco and Luc talk about storytelling around the products their companies make and sell and the importance of knowing and supporting growers.

“Not only is it ethical, not only are we sourcing it directly, we can also make great chocolate,” Luc says. “We don’t need to be a big industrial guy to make good chocolate.”

Indeed, both companies have won international chocolate awards. SOMA purchases its cacao beans from small farms in 15 countries, including Jamaica, Madagascar, Vietnam and the African island of São Tomé, as well as farms in Central and South America.

ChocoSol, which makes eating and drinking chocolate, buys cacao beans from Mexico, the Dominican Republic and Ecuador.

Both companies make a range of bars and confections flavoured with natural ingredients such as fruits and spices.

“In the early days, the hardest thing was educating people about cacao. It still is that challenge,” explains Sacco, who started ChocoSol in Oaxaca, Mexico, in 2004 and opened a factorycafé- store in Toronto in 2006. In Toronto, he runs volunteer programs, internships and workshops. The company also sells products at farmers’ markets and a number of Toronto and Ontario retailers.

“Most chocolate is seen as candy, but cacao is a terrific food,” Sacco says.

“I wouldn’t call it a superfood — I would call it the food of the Gods… a tradition for thousands of years,” he says. Theobroma Cacao, the latin name for the cacao tree, also means the “food of the Gods.” This is also a point of inspiration for SOMA, which translates to “food of the Gods” in Sanskrit.

What makes bean-to-bar chocolate different from the mass-produced version you pick up at the corner store is how it’s made. Bean-to-bar is made from only natural ingredients, without stabilizers or additives.

These products are also more expensive than big-name brands, partly because of their shorter shelf life.

For example, SOMA’s 65-gram, micro-batch bars start at $10. ChocoSol Traders’ 65-gram, stone-ground dark chocolate bars start at $6.

“I hear that a lot,” says Luc of the shocked reaction she gets when visitors compare bean-to-bar prices to candy-aisle bars. Luc leads SOMA’s site tours and educational sessions to explain the chocolate-making process and offer a four-sample tasting.

Starting next year, the chocolate curious can tour SOMA’s new Parkdale production facility. Housed in a former Japanese paper factory, the two-storey location at 77 Brock St. will include a community rooftop garden.

ChocoSol also offers tasting tours, as well as a variety of workshops that get people involved in hands-on learning.

Luc explains the time, effort and cost that goes into producing great chocolate to her tour groups, including the ethics of this kind of chocolate-making.

“We want to work with people who are paid fairly, who are doing good things for our planet and who are making chocolate accessible to everyone. Part of that is closing the loop to bring it back to our farmers,” she says.

Cacao is a labour-intense crop. Farmers harvest the colourful pods, which are about the size of Nerf football and then split them by hand, using a machete. They then scoop out 50 to 70 beans inside, which are covered with a thin pulpy layer. They leave the beans to ferment in the open air for several days. Fermenting is the key to giving the chocolate its musky, funky depth of flavour. Farmers then clean and dry the beans in the sun and ship them to chocolate-makers for processing.

It takes 70 to 80 beans to make a 65-gram bar, Luc says.

The first step is roasting the beans, then winnowing them to remove the shells and smash the beans to create coarse nibs.

The nibs go into a grinder to start the slow process of transforming into peanut butter-like paste.

SOMA uses an 80-year-old Spanish melangeur for this process. ChocoSol uses two stone grinders. If a natural sweetener such as organic cane sugar is being added, it usually goes in then as well.

ChocoSol moves on to tempering after grinding, the system of precisely melting and cooling the chocolate until it’s ready for moulding into bars. The process creates a smooth surface sheen, uniform colour and firm crack when the chocolate is broken.

“Low heat and low time” is how Sacco describes the process.

SOMA usually adds two more steps. First, the cacao paste goes into a ball mill to further refine it (Luc says think of an IKEA ball room, but with stainless steel balls) and then a conch machine, where two cones mix and aerate the chocolate under heat. Luc says there’s some mystery to how the conch works, but the process takes out the bitter elements in the chocolate, perhaps by forcing the cocoa butter over strong-flavoured compounds, to let more delicate tastes come through.

Lindt, which invented conching, is famous for its 72-hour conch, which gives its products a consistent and recognizable flavour profile, she explains.

For its crackle-top Old School dark and milk bars, SOMA skips ball milling and conching.

The basic bars are made from pure cacao, including the rich cocoa butter, often blended with cane sugar or a natural sweetener.

Some versions, such as SOMA’s Arcana Venezuelan Porcelana and ChocoSol’s Gratitude bars are 100 per cent cacao. The intense, layered flavours and silky cocoa butter fat make these the bars to savour in small amounts.

“For some people, it’s bitter,” says Sacco of the 100 per cent cacao experience. “But because it activates your taste buds, everything is a little sweeter afterward. That is what gratitude is.”

ChocoSol Traders

1131 St. Clair Ave. W., Toronto, Ont.

chocosoltraders.com | 416.923.6675 | @chocosoltraders

SOMA Chocolatemaker

32 Tank House Lane, 443 King Street W., Toronto, Ont.

somachocolate.com | 416.815.7662 | @somachocolatemaker