Barbecue Refined

The hardest-working employee at Barque Smoke house is a Tennessean named Dolores. Since the Roncesvalles Village restaurant opened in 2011, she hasn’t had a day — or night — off.

Dolores is the pet name for the 225-kilogram-capacity Southern Pride wood-fired smoker that overlooks the long bar and dining room at Barque. Inside, a Ferris wheel-like rotisserie slowly rotates racks of meats for hours. A deep, narrow firebox on the side holds wood that produces flavour-making smoke, while an automatic gas ignition fires up the logs as needed to keep Dolores at a constant temperature.

Barque executive chef and co-owner Dave Neinstein says the automatic controls let him sleep at night, while Dolores slowly smokes a massive brisket for 12 hours in the empty restaurant.

Although a convection fan vents smoke through the roof when Dolores’ heavy door is opened, occasional light whiffs of hunger-making wood and savoury smoked meat escape as we talk. Two varieties of baby-back pork ribs, one herb dry-rubbed, the other sauce-mopped Alabama-style were finishing their two-and-ahalf- hour “quick and hot” smoking cycle.

Wood smoke, quality meats and Neinstein’s hand-blended, custom spice rubs create a trinity of flavours behind the west-end restaurant’s pit-style barbecue.

He and business partner, Jon Persofsky, started working on the restaurant idea nearly a decade ago. Seeing 30 looming and wanting a change, they packed in their corporate jobs to pursue their shared passion of owning a restaurant. They’d been friends since they met as teenage canoe trippers at a summer camp in Haliburton. Perofsky had the bunk below Neinstein, making their partnership about as Canadian a business start-up story as you’ll find.

Unlike now, where GTA smoke lovers have plenty of Southern-style options, back then Toronto had few places to find an authentic rack of smoked ribs or pulled pork.

They saw a hole in the market, but were unschooled in operating restaurants — businesses that are notoriously expensive to run and even harder to keep open.

Perofsky enrolled in restaurant-management classes, while service-oriented food lover Neinstein, who had taken some general culinary courses, tried to find a mentor to teach him the secrets of pit barbecue.

He met a guy who knew a guy at the Toronto Restaurant Show who arranged an introduction to a barbecue restaurant owner in Ponca City, Oklahoma, population 24,000. Neinstein headed to the town near the Kansas border to work and learn — paid only in staff meals. It was a barbecue-country version of a "stage," the hands-on chefs’ internship.

Neinstein arrived in Oklahoma in April 2010, where, in addition to barbecue, he also learned about tornado season. It’s the time of year when dozens of funnel clouds can charge through an area in a day. The first warning siren sent him bolting for his motel bathtub, clutching his laptop, passport and a bottle of whiskey. He sat there, wrapped in a bedspread, until the tornado threat passed.

Over a couple of months, Neinstein picked up knowledge about rubs, sauces and smoking and discovered the pit master, the employee who tended the smoker, was at the bottom of the pecking order in barbecue country. He also learned by eating barbecue in people’s homes, where most backyards have an offset smoker, and studied to be a barbecue competition judge in Stillwater — about 125 kilometres due west of Tulsa, the state’s second-largest city.

“The competitors were really friendly and they love to trade recipes, tricks and secrets, as long as you’re on the same team,” Neinstein says.

As the only one in the kitchen who had chef’s whites, “they ended up using me for catering and events. I catered the high school prom and the NRA annual banquet just over the border in Kansas City for 1,500 people.”

On days off, he’d drive around and eat barbecue. Neinstein estimates he’s eaten at 80 places across the American barbecue belt, from pork butt in the Carolinas (North Carolina favours vinegar-based sauces; South Carolina is all about mustard), to Texas brisket and “hot links” sausages and wet, saucy Alabama chicken and ribs.

The variety of wood also defines the style. Texas is associated with richly flavoured mesquite smoke. Oklahoma uses sweet, milder pecan. Other regions prefer hickory, which is about in the middle of the flavour profile.

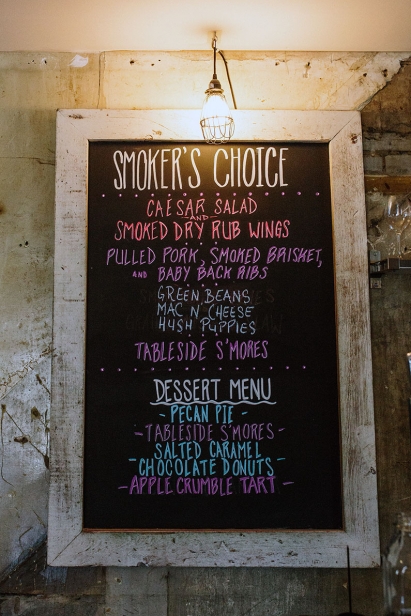

A SAMPLING OF SMOKEHOUSE SPECIALTIES

Smoked pulled lamb shoulder: Neinstein rubs it with Za’atar-influenced spices, including sumac, cumin, citrus, sesame seeds and smoked chilis.

Cooking method: The lamb cooks low and slow in the smoker for 12 hours to ensure tenderness.

The trick: The lamb is tented with foil for four hours at the end to make it meltingly tender. “It’s like tenting a roast and it separates the meat from the bones,” said Neinstein. “It’s also known as the ‘Texas crutch,’ but I don’t really care.”

Sauce: A Middle Eastern influence, with sweet and acidic pomegranate molasses mixed with traditional barbecue sauce elements such as tomato paste, which combine to balance the richness of the meat.

Taste: The pulled lamb is succulent, moist and slightly fatty, although most of the fat cooks off during smoking. Like all the meats at Barque, the pulled lamb is served à la carte with optional sides such as hush puppies, fries or vegetables. Unlike many Southern barbecue places, Barque doesn’t serve bread or buns with its pulled meats.

Beef Brisket: Neinstein takes a fresh, 15-pound beef brisket and trims the fat to less than an inch, a trick he learned from competition barbecuers. He uses the trimmings in the restaurant’s ground meats for burgers.

Rub: Neinstein liberally coats the brisket with spice rub. The exact blend is a secret, but it includes three kinds of peppercorns (green, white and black) left coarse to add crunch.

He also uses granular garlic for more texture. The secret ingredient is coffee.

The trick: The brisket gets its signature moistness by being injected all over with about a half litre of house-made mixture of fruit juice and beef jus. Beef jus with a splash of vinegar becomes its glaze. Then it cooks low and slow for 12 hours.

Sauce: Neinstein says they prefer to allow the meat to speak for itself and the sauce to accentuate it, not the other way around. So patrons can add one of two table sauces — sweet or Carolina mustard.

Taste: Smoky, rich and very tender with bits of crunchy exterior to discover as you eat.

Just as Neinstein had to learn about the secrets of barbecue, Barque staff had to explain this classic food from the American south to Toronto diners who long associated the word barbecue with grilling over charcoal and high heat. Pit barbecues cook food by smoking with wood, in which variants in heat — cold, low and slow, or hot and fast smoking methods — infuse cheaper cuts of meat such as pork butt with flavour.

Diners were initially sending chicken back, thinking the pink near the bone meant it was undercooked. They complained when food wasn’t served hot.

“We had to educate people. It took a while. It was a challenge,” Neinstein says.

The menu now explains smoke and proteins combine to create the pink hue in smoked chicken and that since Dolores never gets above 325F (and can be set as low as 150F), food never hits the table steaming.

As for wood, they rely on “Tony the wood guy,” who clears deadfall and wood debris from roads in Northern Ontario. The cherry, hickory, sugar maple and occasional oak he forages is sold to Barque and other Toronto barbecue restaurants.

Then there are the rubs, crafted and blended by Neinstein himself.

“I spend a lot of time in here,” he says as he leads us downstairs to his basement “office,” where he hand-mixes nine house spice rubs. Each is designed for a different protein, rained on chicken, meats and fish in a thick blanket before they go into the smoker. It took “thousands of dollars worth of meat” for him to develop the different blends, made in 15-kilogram batches. The basement room holds more than 70 types of bulk spices and dried herbs, the bins and packages neatly racked to the ceiling.

The rubs are made for both kitchen food prep and retail. Down the street at a second Roncesvalles location, The Barque Butcher Bar — a restaurant, retail outlet and catering kitchen — there is a large wall unit with drawers holding a variety of herbs and spices for people to make their own custom rubs.

The formula Neinstein uses is based on three parts sugar (brown and white) and salt in equal amounts, two parts herbs and spices and one part of the most “assertive” spice in the mix, such as cayenne or cloves.

Sugar is crucial. “It helps to create a layer of liquid that will cook the outside of the meat and helps the other spices stick to it and it also balances out the taste palate,” Neinstein explains.

Texture also comes into play, so some spices are coarsely ground to create a crunchy crust. That crust is called “bark” by barbecuers and gives the restaurant its name.

While Barque serves a variety of barbecue styles, including Memphis, Alabama and Texas, “this is Toronto barbecue,” Neinstein says. “Local ingredients, but with flavours from around the world.”

So smoked salmon has a maple glaze and there’s Chinese barbecue sauce on the smoked Shanghai duck tacos. “Greeque” Salad features smoked feta, while smoked lemons are used in salad dressings as is candied smoked bacon. Smoked pineapple and mayonnaise-based Alabama white barbecue sauce enlivens Korean BBQ nachos. Clearly Neinstein means it when he says, “We’ll smoke anything.”

Barque Smokehouse

299 Roncesvalles Ave., Toronto, Ont.

barque.ca | 416.532.7700 | @barquebbq

Barque Butcher Bar

287 Roncesvalles Ave., Toronto, Ont.

Barque Smokehouse

4155 Fairview St., Burlington, Ont.